Story and photos by Steve Guntli

While finding funding for the new Whatcom County Jail facility has been a contentious point amongst county legislators, the one thing county officials agree on is that a new jail is necessary.

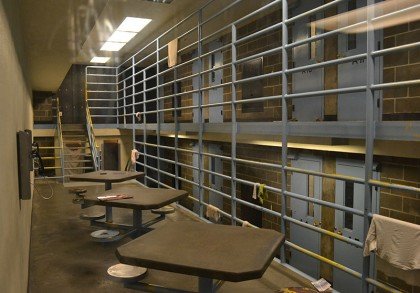

The current jail was born out of date: built in 1983, it complied with state standards in place since the 1960s. The facility was originally built to hold 148 inmates, but remodels and retrofits over the last three decades have raised the bed count to 280. And that’s still not enough: on average, the building holds about 350 inmates, according to a report by Whatcom County Sheriff Bill Elfo. In 2013, a county jail planning task force determined the need for a new jail was “critical” due to overcrowding and unsafe conditions.

I was part of a small group of media delegates and local government officials invited to tour the facility in downtown Bellingham. A new county jail facility is in the planning stages, and voters will have a chance to approve the county’s jail plan during this November’s general election. That plan looks increasingly likely to proceed without Bellingham’s help, as the city council balked at a financing plan that proposed a 0.2 percent sales tax increase. The county has developed plan B, reducing the proposed size of the facility from 521 beds to 400, at a cost of about $75 million.

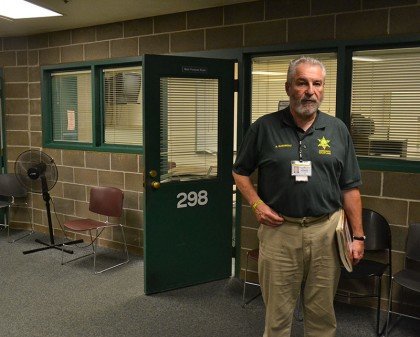

Our tour guide was Ray Baribeau. Baribeau is an associate chaplain at the jail. He’s been working with inmates for most of his adult life. He’s pleasant and unassuming, but beneath the genial surface is genuine frustration at the poor quality of the facility.

Before the tour began, Terry shared a pamphlet showing the SCORE (South Correctional Entity) regional jail in Des Moines, Washington. Whatcom County is consulting with that facility’s designers on its new facility in Ferndale. The pictures depict well-lit, wide-open spaces, top quality medical facilities and floor-to-ceiling windows in the lobbies and employee break rooms that flood the rooms with natural light. It was a stark contrast to the facility we were to walk through.

The employee break room sets the tone. Three small tables and two ratty couches are haphazardly crammed together around a small flat screen TV, jammed between a row of banged-up lockers and an oversized vending machine filled with energy drinks. The only glimpse of natural light comes through a row of tiny, opaque windows that line three of the walls near the ceiling. An officer jokes that they have the second-best view in the building, after a cell in the third floor solitary confinement. The only difference is you can see out the windows in the solitary cell.

row of banged-up lockers and an oversized vending machine filled with energy drinks. The only glimpse of natural light comes through a row of tiny, opaque windows that line three of the walls near the ceiling. An officer jokes that they have the second-best view in the building, after a cell in the third floor solitary confinement. The only difference is you can see out the windows in the solitary cell.

The rest of the jail makes a similarly ignominious impression. The elevators lurch and judder uncomfortably as they slowly change floors. The fluorescent fixtures are cracked and flickering. Paint is chipped, concrete cracking; the lettering on some of the doors has worn away, and in some places was hastily redrawn with magic marker.

We visit one of the first-floor dormitories, called “tanks.” This tank has about 10 bunks and an open floor space. Inside, men gather close to the window and start making zoo animal noises.

“Y’all here to see some criminals?” one shouts. “Take a good look.”

This tank was originally designed for men’s work release, but was converted to house overflow. Up to 30 people can live in each of the dorms at a time. Baribeau is critical of the dormitory system.

“Dorms like this are a recipe for trouble,” he said. “You put a bunch of guys together, and even if they’re normally well-behaved, they’ll start needling each other, and that’s when things get violent.”

The problem is especially acute when sex offenders are brought in amongst the general population. Baribeau said sex offenders tend to be well-behaved when kept on their own, but are targeted when put in large groups. Now, most sex offenders are kept under heavier security on the second or third floor, as much for their protection as anything else, but sometimes there just isn’t space to segregate them.

The better method, Baribeau said, is “pod” cells, two people per room united by a large common area. The SCORE facility from the pamphlet used this design.

The kitchen is a long, narrow space on the first floor. The floor, a rust-colored rubber surface, is only about three months old. The county paid to put it in after the health department found the cracked, worn tiles too much of a slipping hazard. About a dozen inmates are working in the kitchen, music blaring. They politely turn the music down as Baribeau leads the tour through, and proceed to mug for the cameras and joke with us. These are minimum risk inmates, what would once have been known as “trustees,” and they’re given a lot of leeway for their good behavior.

The kitchen facility was designed to serve 145 prisoners three meals a day. The kitchen manager tells us they now make 370 meals three times a day, including the 135 meals they send to off-site work groups. A spare room had to be converted into bulk food storage to deal with the demand. That room is located on the third floor, on the opposite end of the facility, so crews haul carts there and back a few times a day.

The food storage isn’t the only space that’s been repurposed. Baribeau is constantly pointing out rooms that used to be this or were converted from that. The first-appearance courtroom on the second floor was once the commissary, where inmates could buy snacks or decks of cards. A room once designated solely for GED classes is now the multi-purpose room, hosting Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous and Bible study groups in addition to GED classes.

We come across a stack of thin mattresses resting in long plastic trays. These trays are called “boats,” and they’re used when the jail is over capacity and inmates need to sleep on the floor. The mattresses are thin, and most are torn at the seams and spewing wads of cotton.

“If you have two people in a cell and need to add a third, that third person is called the ‘rug,’” Baribeau said.

Medium- and maximum-security cells are located on the second floor. It’s after 5 p.m. when we take our tour, so most of the inmates are on lockdown, but some are left to roam the racks, if only to collect their medication from nurse Brady, a cheerful man in his 20s.

to roam the racks, if only to collect their medication from nurse Brady, a cheerful man in his 20s.

Baribeau is well liked amongst guards and inmates alike. He teaches Bible study a few times a week, and knows most of the inmates by name. He chats with some of them on our tour, his tone shifting from amiable to disappointed when he sees a familiar face back behind bars.

One inmate, secluded in the sex offender’s block, kneels close to the ground to chat with Baribeau through the food tray slot. He explains to Baribeau that he’s on his way to prison.

“For the same thing?” Baribeau asks. The inmate nods.

Inmates on the second and third floors have most of their conversations with the outside world through those food slots, unless they’re using the visitation cells located on each floor. Baribeau jokes that old guys like him have learned to bring a stool to spare their knees.

Officer Tim Kiele pauses the tour and invites us to come into the control room. He’s enthusiastic and friendly, and the few times he interacts with inmates over the intercom, it seems he’s well respected by the population. The county spent $3.5 million to update the control center five years ago. Kiele said the new system is a huge improvement over the last, but he still has concerns over some of the antiquated wiring.

“As far as I’m concerned, this new system is a band-aid,” he said. “We still have to address the wiring and the floor plan. If there were ever a fire, all of these guys would be gone.”

Baribeau echoes this sentiment later in the tour.

“There are two things you pray for when you enter this building,” Baribeau said. “No earthquakes and no fires.”

The fire escape routes, which are far too narrow to easily accommodate the population, are located at the far end of the hallway. Each floor has several cracks along the surface. In one section, a small gauge used to monitor seismic activity and structural integrity has been placed over a crack like a band-aid.

While Baribeau was critical of the facility, he had nothing but praise for the jail’s employees.

“These people work so hard every day, and believe me, this is not an easy job,” he said.

We arrive on the third floor, which houses female inmates and the solitary confinement wing. “Solitary” proves to be a bit of a misnomer: most of the solitary cells, which by design are meant to keep antisocial or violent offenders away from the population, have been modified to house two or more. Only the most extreme cases are actually isolated. One room, the one the officer described as having the best view in the building, is meant as a shower facility for solitary inmates. When we visited, four men were sleeping on bunks in the room. Baribeau seemed perturbed by this, since beds were available elsewhere.

Near the solitary wing were two tanks used to house inmates with severe mental or physical health requirements, or those in protective custody. The medical facilities are located on the second floor.

“It’s criminal that we have people with medical needs on a different floor from the medical facility,” Baribeau said.

The medical facilities have two examination rooms and a small staff of nurses. A psychologist visits the facility a few times a week. Whatcom County Council has promised more money for mental health and prevention programs in the new county jail, with 8,000 square feet earmarked for mental health facilities.

Baribeau leads us back downstairs, joking with guards on our way. Squinting at the sunlight outside, we depart, grateful to be out and that we all have better views to look forward to than the guards at the Whatcom County Jail.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here